FiLiA

FiLiA is a UK-based feminist charity, platforming and connecting women through our annual conference, blog posts, and podcasts. Listen to women sharing stories, wisdom, experience, feminism, sisterhood and solidarity. Find us at: www.filia.org.uk

The opinions expressed here represent the views of each woman. FiLiA does not necessarily endorse or support every woman's opinion, but we uphold women's rights to freedom of belief, thought and expression.

FiLiA

#188 Woman! Life! Freedom! The Women-led Revolution

Use Left/Right to seek, Home/End to jump to start or end. Hold shift to jump forward or backward.

Maryam Namazie is an Iranian-born campaigner and writer living in the UK. Since the Islamic regime of Iran’s killing of Mahsa Amini on 16 September 2022 for ‘improper veiling,’ Maryam has been speaking on and organising protests in solidarity with the women’s revolution in Iran. FiLiA have joined Maryam launching the Hair4Freedom campaign and are continuing this relationship with our next solidarity action #Dance4Freedom on 29 April 2023 which is discussed in this episode.

Freya: My name is Freya, I'm a campaigner and activist for FiLiA, and I've been lucky enough over the last few months to be working with Maryam Namazie, on our joint action Hair for Freedom. Maryam Namazie is a spokeswoman for One Law For All, and the Council of Ex-Muslims of Britain. She's an Iranian-born campaigner and writer living in the UK.

Since the Islamic Regime of Iran's killing of Mahsa Amini, on the 16th of September 2022, for improper veiling, Maryam has been speaking and organising protest in solidarity with the Women's Revolution in Iran. Thank you for joining us, Maryam.

Maryam: Thank you for having me, and it's such a pleasure, as always, to be talking to you and to be working with FiLiA.

Freya: We've really enjoyed working with you with our Hair for Freedom protest, and we have another one coming up on the 29th of April, which we're asking all of our FiLiA supporters and podcast listeners to attend, to show your solidarity with Iranian women. We'll talk about that protest towards the end of this interview.

I'd like to start, if that's all right, with a bit of a history of Iran, and how we have gone from revolution in the seventies to today's women's led revolution, and what has happened in between. We see so many images of Iran in the seventies with women unveiled, and with women at university, talking about an incredibly different life. I wonder if you could tell us a bit about what Iran was like back then.

Maryam: Yeah, yeah. There are very stark differences, aren't there? When we look at photographs of women in Iran before the establishment of an Islamic regime. Obviously, women didn't have to wear the hijab, and they could wear whatever they wanted.

But I think it's important to note that even though there were those, sort of, personal freedoms, like you couldn't be arrested for dancing as you are today in the Islamic regime of Iran, you had certain personal freedoms, it was still a dictatorship. So I suppose it's kind of like, you know, the Assad dictatorship in Syria, it doesn't have compulsory veiling, but it's still a dictatorship.

So during the Shah's time, there was political prisoners, there were executions, tortures, and a lot of repression of people who were dissenters or free thinkers. The revolution was a, sort of, a challenge to that dictatorship. So the ‘79 revolution was a people's movement against the Shah’s dictatorship.

It wasn't an Islamic revolution. It was a revolution for freedom and against the Shah’s dictatorship, but unfortunately it was hijacked, really, by the Islamic movement. And if you know the context of that period, it makes sense why that happened. And in a sense, I think what's happening today in Iran is a continuation of that unfinished business, you know, of a revolution for freedom and equality that never really came to fruition.

And now a new generation has taken up that banner against the Islamic dictatorship.

Freya: That's a really interesting history, to know that even though we might see pictures of what seems like a freer Iran back in the seventies, that it wasn't necessarily the case, and that images can be deceiving. So what was it, how did the Islamic regime hijack the revolution back then?

What was it that made people support that regime?

Maryam: I think if we remember that this happened in 1979. It was during the Cold War, if you recall. And, it’s so funny, it's recent history, but it seems so long ago, and people don't necessarily remember. I think there is this historical amnesia that we all have that makes the past look a lot rosier than it was. And that can be quite dangerous because I think that's why we often find that history repeats itself.

So it was during the Cold War, and it was part of Western government policy to create a green belt, or an Islamic belt, around the Soviet Union at the time. So if you remember that part of history, for example, the US was involved in providing both military training and hardware to the Islamic mujahideen in Afghanistan, and also they met in Guadalupe.

Now, this is all public information now. It wasn't before, but a certain time period has passed, and now this is information that's available to the public. They met in Guadalupe, and decided that they prefer an Islamic state to a left-leaning revolution.

And so it was part of that foreign policy that brought Islamists to centre stage, even though they were not - they were on the periphery of politics really - but they were brought to centre stage. And that is how, in a sense, a revolution for freedom and against the Shah’s dictatorship ended up being considered an Islamic revolution and being called an Islamic revolution, whereas in fact for the Islamic regime to get power, it had to kill a lot, a lot of people.

So really the slaughter of an entire generation. And that has continued for many decades now. And so… and again, I think anyone who knows about Western government foreign policy, it's not surprising is it, to find out about interventions. We know about interventions from, you know, all over the world, more recently, but also, you know, in Latin America and in Africa and in Asia. I mean there's a history of that, sort of, intervention.

Also in Iran, you know? And so I think it's not surprising, but it's quite worrying, isn't it, that when people's revolutions take place, that they can so easily be destroyed. And how fragile is this demand for change, by people from below? And I think what is even more worrying is that we're seeing that, sort of, intervention now, as well, in this Woman Life Freedom revolution.

We're seeing the, sort of, intervention from above with the collaboration of Western governments. The Shah's son, the former dictator’s son, is now putting himself forward as the alternative for an Iran after the Islamic regime of Iran, and it’s very, very worrying.

And, you know, for people who can't understand how the Islamists took over from the 1979 revolution, I think if they look at what's happening today, they can see how easily that can be done, and how vigilant we need to be if we're going to help get this Woman Life Freedom revolution to fruition, to actually be real change for women's lives, in Iran and the region. Or is it going to be just changing regime, from above, from dictatorship to dictatorship?

Freya: Thank you for explaining that, and you're absolutely right, we can see that today, with the negotiations with Russia being another, you know, rising again with what's happening in Ukraine, and the meetings that we know are happening between certain countries and certain dignitaries to shape what is going to come for the next 44 years. And you are right, it's down to those that remember to remind those that don't of what happened before and what could come again.

So in the wake of the 1979 revolution, and the clerics, the Iranian regime, taking over, what happened over the next, sort of, 30 years, that certainly led to people like yourselves leaving Iran and spreading the word as to what was happening back home?

Maryam: I mean, at the initial stages of the revolution, it was a very free society, in the way that we hadn't seen in recent memory. So there were lots of protests, and books being distributed, and discussions and debates on every street corner, and it was that sort of solidarity and support you see at revolutionary times, like we're seeing today in Iran.

But again, once the Islamists started taking over, it was… you know, you could kind of see changes taking place overnight, and that spring that everybody was seeing, coming to a quick end. So, you know, I think when the religious right take power, obviously one of their first targets are women. It's always the case. They come for women first.

So it is, you know, you see that very much so in the public space. In a way it makes a very quick, you know, it very quickly shows that there is change, for the worse. So it includes, you know, for example, magazines with women's bodies being blacked out, or their faces being blacked out.

And you saw that also with the Taliban coming in Afghanistan, how they started just blacking out women's faces, their bodies on advertisement, on magazine covers. And of course, this idea that women now needed to wear the hijab, they started by saying that women who work in government offices need to wear the hijab, and it has to be compulsory or they would be fired.

And on March 8th, 1979, it was a mass International Women's Day gathering in Iran, to protest this new rule, because it was on the verge of them taking over, and it was part of this protest to resist them. And tens and tens of thousands of women came out into the streets shouting, you know, “neither Eastern nor Western, but women's rights are universal.”

And there were both veiled women and unveiled women shouting against compulsory veiling. So it was, you know, if you see video images of that protest, it is inspiring and just unbelievably wonderful to see. But again, it was completely suppressed. So the regime came with the slogan, “you either wear the veil or you will be punched,” and women were physically attacked, at the protest, and throughout, including, for example, by throwing acid in women's faces

The Islamists actually pinned the hijab on women's heads with pins, as a way of enforcing. So it came with huge amounts of violence. And we know even today, when you see videos of morality police arresting women, there is so much violence attached to that arrest, and that imposition of the veil.

And that was something that started, you know, with the attempt of the Islamists to maintain power. And I think, well obviously, you know, given the fact that the veil and sex segregation are the most visible aspects of their rule, them coming for women was a way of suppressing all of society by suppressing women.

And in a way we can see conversely how today, the liberation of women is going to be, and is, so key for the liberation of all of society, and it goes around the issue of the veil again, because that's exactly what they started with as well.

Freya: So I can tell there's a long history of women protesting, and specifically women being targeted, in Iran then. Which I guess is why, when this revolution erupted, that it was women-led, and that it was about women and what was happening to women. Were men in 1979 on the street supporting women like we see today? Or has that been a slower process?

Maryam: I think one of the things that we find very different today is that men are very much standing up with women, and shouting Woman Life Freedom, and risking their lives for this revolution. So a lot of those who've been executed are men. A lot of those in prison, tortured, are men and those who've been shot at protests.

It wasn't the same in 1979, and I think at the time, and I'm someone on the left, a lot of leftists were saying that, “the issue of the veil is a trivial matter, it's not a key issue, and it's a deviation of the revolution's aims, and therefore, you know, it's not something that we should be discussing right now, there are bigger issues at stake.”

And what's clear today is that there is no bigger issue than women's rights, because it is the way in which the regime has suppressed society. And if women are free, the society will be free too. And so I think you can see very clearly that there is that shift. And of course, that shift has taken 44 years because of the work of women's liberation activists and campaigners and that movement in Iran, that has brought society to this stage.

Still, of course there is pushback because, you know, I think all societies are patriarchal, we know that, and particularly those that are theocracies. And so there is a lot of pushback still, in various ways, including, for example, the attempt to bring the slogan, “man, nation, prosperity,” as a sort of challenge to Woman Life Freedom.

But of course it hasn't become comprehensive in the way that Woman Life Freedom has, because obviously it's an absurd slogan. It's ‘more of the same’ slogan. There are attempts of that nature, or criticisms often, that I receive, for example, “stop making it about men and women, you know, stop dividing it, stop calling it a woman's revolution.”

You know, “we men are giving up so much for this, and it's not for women only,” and this and that. And again, it's interesting, because of course not all men are misogynist, but all men have been privileged by these theocratic rules and sharia rules. And they never talked about, “don't make it about men and women,” before, when women were being suppressed and segregated and had lesser rights, were seen to be inferior, on par with animals.

That's exactly how women are viewed, you know, at one of the Friday prayers leaders said, “God has made different types of animals for different purposes, some animals have been made for transport purposes, some animals have been made to feed people, and other animals, like women, have been made for men's use. And the reason that they look like human beings is so that men aren't frightened by them when they're using them. And that's why they've been made to look human. But they're no different than animals.”

And this is propaganda that the regime has been spouting for, you know, more than four decades, so obviously it has an impact. But what I find, you know, if we look at - you know, as an activist, I'm always an optimist and always look at the glass half-full rather than half-empty.

And I think that, how amazing that despite all of this propaganda, despite the fact that the generation that's on the streets today have only known an Islamic regime, have only known a theocracy, and how modern, how secular, how woman-centred they are, is really a testament, I think, to the human spirit, to, sort of, refuse and resist despite all that pressure and intimidation.

So I think, you know, it’s a huge step forward, and a lot of work still will need to be done, obviously, and will continue to need to be done, not just in Iran, but you know, we know, across the globe, including here in Britain.

Freya: Absolutely. That's such a common thing that we hear, about men on the left saying, “not now, now's not your time, your time will come, but we've got more important things to deal with,” and very much so the, “why are you making it about women.”

And women speaking, we've seen just this weekend, protests across the world of women speaking, regardless of where they come from, what their background is, and what they're speaking on. So it’s actually been, certainly for us here in the UK, watching the women of Iran stand up, fight back, and the men to stand at their backs and fight with them, has been incredibly moving and incredibly optimistic to see that that is possible.

So you’ve given us a glimpse of optimism actually, by seeing what's going on in Iran at the moment, even under such terrible circumstances.

Maryam: Yeah. I mean, I think really if we want women's liberation, men have to be on our side as well, you know, and in the sense that this is their fight too, it is for their own freedom as well. And I think one of the things that's so wonderful about this is that men are coming on board as well. And I think it does, that also makes it inspiring, that it's not just women fighting for women's rights, because very often that's how it's always been.

It's always women fighting for our rights very much without, not just not having other people's support, men's support, for example, but also, being silenced or being told that, you know, “this is not the fight that matters or, you know, this is not the time for it.” There's never, it seems it's never the time or place to fight for women's rights. There's always more important things.

And I think, you know, this is a hugely - and I think that's why, in a way it's been so inspiring too, because we're seeing that it's a revolution against a theocracy, but the main slogan is Woman Life Freedom, and we don't want a misogynist state. And that's, you know, how can you not be inspired by that?

Freya: Definitely. Woman Life Freedom. That's a Kurdish saying, am I right? And is there a history behind that?

Maryam: Yeah. In fact, Woman Life Freedom was first raised in Rojava, which is a Kurdish area in Syria, and it is a feminist centre in a war zone. So, you know, Rojava is really the first women's revolution in our region, in the Middle East.

And here now we have another revolution in Iran, which is again, calling for Woman Life Freedom. So possibly we could be seeing the beginning of women's revolutions in the region, and that region could be a new centre of feminism. You know, when we were always told feminism is a Western concept, well, obviously Rojava and the revolution in Iran show that it's very much a universal demand for women everywhere.

But we could be, a few years down the line, looking at that region, that was always a centre of misogyny and femicide, you know, to be… imagine if, in a couple of years, it becomes a centre of feminism for people across the globe. It's possible, I think, given where we're heading, but of course it needs to be supported, nurtured, encouraged, strengthened. Otherwise, you know, there there's no guarantee of victory.

Freya: Absolutely, and that's something that we'll all be watching quite closely, and hoping that it continues the way it does, and it doesn't get shut down and it doesn't end up being another… I know the term from back then is ‘the failed revolution,’ but another failed revolution this time around.

So the difference with this one, if we go now to what happened, sort of, six months, just over six months ago, with Mahsa Amini. So for those that perhaps haven't followed so closely, Mahsa Amini came to visit the capital of Iran with her family, and whilst there, I think she'd been there all of five minutes before she was approached by the religious police and arrested for incorrectly wearing her hijab, I believe they said, which would mean anything from a strand to a few strands of hair being shown.

And then a report’s come out just recently to say that she was arrested along with several other women, taken to a police station, and beaten. And when in that police station she collapsed, and for 45 minutes they did nothing, until eventually the paramedics came, but unfortunately it was too late and she died.

These sort of acts seem to be, from what I understand, have been happening regularly. Women have been being pulled off the street and beaten. What was it about Mahsa Amini’s case particularly that sparked this moment? Was it just it was a straw that broke the camel's back, or was there something specifically around this moment?

Maryam: I think with her case, it's, you know, as you said, it's the sort of, arrests and beatings and violence is something that I would think that there's no family in Iran that hasn't had their girls, daughters, you know, sisters, mothers, not faced or had a run in with the morality police. I think there won't be a family you could find in Iran.

And it's so distressing, and it's so humiliating, and you are dragged off with such violence, and threatened, and of course there's also evidence of sexual assault, and abuse, and even rape, and that's also coming out more recently with regards to those who have been arrested.

So I think partly it has to do with the fact that it was the last straw that broke the camel's back, in the sense that it's happened so many times, but it was just so outrageous what had happened to her. And the fact that news spread very quickly because two women journalists actually brought the case to the public. And imagine, since September 16th, they are still in prison, under national security charges, which means, could mean, decades of imprisonment. They're still imprisoned, merely for raising the alarm and saying what happened to her.

But also I think it goes back to the fact that, you know, she's a Kurdish woman. Woman Life Freedom originated in Rojava. And it is that resistance that we have always seen in Kurdistan. And it was very evident in her funeral, you know, her gravestone said, “you won't die, your name is going to be a symbol.”

And it was that, sort of, that resistance, that took place at her funeral, which had nothing to do with usual religious mourning ceremonies, and all about defiance and resistance and support and solidarity. And we've seen that now in all the funerals. You know, they are not centres for mourning, and religious mourning, but for defiance.

And applauding the person who's been killed, shouting slogans, they are political, dancing, political gatherings, to put further pressure on the regime. So I think… also though, we have to remember that there's been constant protests in Iran, you know.

And protests have been going on for many decades. Some of them really shaking the regime. The difference this time I think is possibly, one, that the protestors are from a generation that have no illusions towards Islamic rule. Cause in the past there was support at some protests for the reformist faction of the regime. Those who were called the reformers, the green movement.

What we argued then was that they are not real reformers, because reform means changes in the law. You can't be a reformer and still have Islamic law that stones women to death and imprisons you for the veil. You have to have real changes in the law to be called a reform movement, and that it was really a strategy of the Islamists, in order to maintain power.

Because it's so explosive, the situation in Iran. People are so fed up with Islamic rule that they felt if they, as a strategy, bring a reform movement that seems to be not as harsh as the conservatives, that it will remove some pressure from the regime. And it did for for a while. So it was a successful strategy.

But now people have realised that there is no way you can reform a theocracy. It's like trying to reform Nazi Germany or trying to reform the racial apartheid regime of South Africa. It's unreformable. It has to go. All of it has to go. It's just an abomination.

And so I think it's this generation too that is not accepting any aspect of the regime, that's anti clerical, even has anti-religious strands, and is very much woman-centred and for women's liberation. And so I think, in a sense, even if it fails, and it won't fail, we won't, we can't allow it to fail. But even if it fails, society can never go back to what it was.

And I think that is the thing about revolutions. It may not happen right away. It sometimes is a process; it can take years. But today there are so many women walking unveiled in the streets of Iran, even though there are still morality police, even though compulsory veiling is still the law, because things have shifted and you know, it's thanks to this revolution.

And, you know, so I don't think a failed revolution could ever - we could ever call it a failed revolution, but we hope that it can be a successful one.

Freya: We’ve certainly seen images come out of what we would, what you would consider conservative women joining the revolution because they've had enough, women that have happily worn the hijab and happily supported the regime for a very long time, who've had their granddaughters murdered or beaten or kidnapped by the morality police, who are now saying enough is enough, and Woman Life Freedom. So I have faith, like you, that this won't be a failed revolution.

But then we see footage coming out, not so long ago, of schoolgirls being potentially gassed within their classrooms. There's been I know a lot of back and forth as to who's responsible, what's actually happening, what's real, what's not.

Obviously, you know, “the girls must be hysterical and it must not be real,” is the line that's coming out in a lot of articles, and we've seen that time and time again. I wonder if you can share a bit about what you know is happening right now in Iran, especially with this revelation that it does seem that schoolgirls are being targeted, cause schoolgirls have been very highly featured in the protests, haven't they?

Maryam: Exactly. I mean, if we look at the images of the protests, it’s very, very young girls, and also schools have been centres of resistance, so protests within schools, throwing out regime officials from schools. And you know, in Iran, first of all, all schools are segregated, and girls have different textbooks from boys because, you know, they're different. They don't need to learn the same things.

But also every school, including primary school, has a paramilitary force in there, so a member of the Basiji, or the revolutionary guards. There is a representative in all schools to spy on students and to control them. So to think that despite those, sort of, forces of repression in every school, that nonetheless schools and school girls have been at the centre of these protests, just shows, you know, how brave they are really, and how much of an effect they've had.

And so we know poisonings in school started in November actually, but it was a few, it wasn't as many schools, but it's reached a point where as many as 5,000 students have been taken ill with respiratory problems, nausea, lethargy, headaches, and it's after smelling some strange odour in the school, and it's been in over 230 schools across 25 provinces.

So a majority of provinces in Iran, and human rights groups have said that it could be up to 7,000 school girls who have been affected. So 5,000 is just, sort of, the official number. And there's been a lot of video footage of families who've gone in front of the schools to protest, who've been brutally beaten by, and arrested by, the regime.

And of course part of it is, you know, at first we heard that it could be hysteria. And that's so typical, isn't it? It's always, when it comes to girls and women, suddenly, you know, it's a question of hysteria. There's no real reasons why this could be happening. And again, the misogyny behind that as well, is something profound that we really need to look at as a world and in our societies.

But we know also some boys’ schools have been affected. And when that happened, women's rights campaigners were saying, “well, I guess it's not hysteria now, is it?” You know, because some boys’ schools have also been affected. The regime says that they've arrested 110 people, who might have had a hand in these poisonings, and of course it will be their own people.

I mean, we don't even know who these people that they've arrested are, which is interesting, and a lot of people are saying on social media, you know, someone burns their hijab, they've got facial recognition technology, they arrest them the next day and they're in prison being tortured. And here there are all these schools in all these provinces, and it took them so long to arrest people. And that's just really because of public outrage in Iran as well. Mainly in Iran.

Now they've arrested 110, but we don't even know who these people are, which is not like them cause they're usually parading people they arrest and having them confess. A lot of the, you know, a lot of people who are protested, they try to make them provide false confessions under torture on TV, et cetera, et cetera.

So clearly it's their own policy, as an act of revenge, as an act of trying to instill fear. But what I find interesting is that really this generation doesn't seem to want to back down, and it's refusing to back down. And there are so many examples of this that are just mind boggling, how under those circumstances, people, girls, women especially, continue to resist.

And I just want to give you one example of this. There's this labour rights activist and a woman's rights campaigner. Her name is Sepideh Qolian, and she was released just two weeks ago, the 15th of March, and she was in prison for five years and seven months for defending Haft Tappeh workers in Iran.

She's just this amazing woman who often is photographed without her hijab, and as her family met her in front of the prison, she shouted a slogan that was videotaped and then it spread on social media. She said, “Khamenei the tyrant, soon, you know, we're going to get rid of you, we're going to bury you.” So on her way home, she was rearrested and taken back to prison.

So, I mean, you think, my goodness, like she can't even wait till she's home to make a comment. You know, it's that defiance, and that resistance is what has the regime so scared that it is trying to poison girls at school, and they're not able to push that defiance back.

Freya: It's quite wonderful to see, even though it is heartbreaking and worrying and concerning when you see those images, I do remember seeing that on Twitter like you say, maybe sort of 10 days ago, two weeks ago, and I wasn't sure what she was shouting, so I'm glad you've shared that. So yes, it is heartening. There's only so many people you can throw in prison.

And that's why we want to show our solidarity from afar. There's only so much we can do here in the UK as your feminist sisters, so that's why we decided that the Hair for Freedom action would happen. We wanted to show Iranian women that we supported them, that we are in solidarity with them, and to put pressure on our government here to be firm with sanctions, and to hold the line, and to hold Iran to account.

So the Hair Freedom campaign which we collaborated on and that we did last year, started last year in a wonderful action at Piccadilly Circus where women came and cut their hair. So, first off, can I ask you why cutting hair became such a symbol, what was it about cutting hair?

And then for your reaction to that wonderful, sort of, hour - hour and a half that we spent in Piccadilly Circus, the music, the history of the drumming that was being done, the chants that were being chanted, the dancing that was being done. I know it's a moment I'll never forget. What was it like for you?

Maryam: I mean, it was one of the most beautiful, wonderful protests I've ever been to, and that we've ever organised together. I think it was just wonderful and I think it was very moving, and you could see how, so many women cutting their hair, it felt so emotional, you know.

Because in a sense you think this hair is something that women are being killed for, and then women coming and cutting their hair, in solidarity with women being killed for showing a few strands of hair. I think it's a very powerful thing to see and to be part of, and it's one way of women showing their support and solidarity, because I guess for a lot of women and a lot of people, their hair is, you know, important to them.

It's part of who they are, and cutting it just shows that, you know, there are things that are more important than what we find important for ourselves personally. And what's interesting is we then decided we were going to throw that hair on the Iranian embassy and we had gathered all this hair and we went there and the police didn't let us go to the embassy. They blocked us off, so that we could only have a protest a little away from the embassy.

And the policeman said that if we threw the hair on the embassy, it would be distressing for the embassy. And it's interesting, you know, that the police, even here, recognise how distressing women's hair is for the regime, but for the regime to be protected rather than women, again, is the story of our lives, isn't it?

And just came to prove how much support the regime has, even from the government here, and how little women have support, and that's why we really have to rely on each other, and it's our solidarity with each other that can make a real difference.

Freya: Yes, it certainly felt, that second day when we were going to throw the hair, that absolutely the police were there to protect the embassy, to protect a building and the men inside the building, from women's hair, more than our right to protest.

And it is quite shocking. Obviously, you can't compare what's happening in Iran with what's happening in the UK, they're very different places with very different experiences, but the laws cracking down on protest here in the UK, when you start to realise the impact they're having and the effect they're having, and that they're shutting down so much protest.

It is just so simple. And so it's not violent, it's not, aggressive as you say. I mean, distressing - is throwing hair at a building really that distressing?

We have plans for what to do with the hair, certainly. I know I've had a go at creating some art with it, so watch this space and see what happens. And actually, that's something I'd like to pivot to. There's been some wonderful art that has been created, I can see, quite a lot of it behind you. I know this is a podcast, so no one else can see what I'm seeing, but Maryam is surrounded by Iranian art behind her, some of which I've seen on protests with you.

What is it particularly, why has the art been such a key part of this protest? Again, is that something that's cultural, historical, with Iranian women and Iranian culture?

Maryam: I mean I think revolutions are groundswells of creativity, and it is why we've got such wonderful new revolutionary songs, a lot of them about women's rights and very much women's rights centred, and art that's very much woman-centred. And I think it's because of, you know, the fact that it's a Woman Life Freedom revolution. This wasn't the case at other protests that have taken place over the past decades.

So I think it is, there's something about revolutionary periods that really cause this flourishing of creativity and we know music, art, they're so key to protest and to revolutions, and so I think that's why we're seeing this in a way that we hadn't seen since, you know, the 1979 revolution.

Freya: Music and dancing has certainly been suppressed, hasn't it, for women in Iran?

So I know the drum that you play is a very particular type of drum, a drum that women aren't allowed to play in Iran, and that you hold a drumming group where women are able to not just play the drum, but have music written for them, specifically to be able to play the drum as a form of protest. I wonder if you want to share a little bit about that?

Maryam: Yeah, I mean, it’s interesting. The thing is that in a theocracy and in Islamic theocracy, when we know that women are targeted, it targets every aspect of their life. So their voice, for example, is banned. So women cannot sing in public, and women cannot dance in public, either.

And so this sort of - and women can't perform on stage - so it is sort of, you know, theocracies are the death of not just democratic politics and free thought and expression, but also the death of women's creativity and voice, as well as bodily autonomy and all of that.

And so you are seeing in Iran, these women, you know, going into a mosque and singing, or singing at protests, dancing at protests. I mean, dance has been really key. Dancing at funerals. It's so key. And also women singing, at protests, at funerals. It's been very much part of that, sort of, resistance and defiance that we're seeing.

And of course, you know, those of us who are in the diaspora, also try to show our solidarity and support, by doing the same here. Obviously, we are free to do it here. But it’s all about how we can extend what's happening there to the public in the countries that we live in, outside of Iran, in order to, sort of, mobilise solidarity, support, raise awareness, keep focus on the issue, because people forget very quickly, don't they?

It's like, gosh, very, very short memories. We move from one tragedy to another. And, this is such a key moment in Iranian history, that's not just key for women in Iran, but for women in Afghanistan, for example, and also in the region and elsewhere. And so it's really important for us to be able to keep pressure on.

I do want to just also talk about a few other things that people can do. I don’t know if that's okay.

Freya: Of course.

Maryam: You know, well, I guess we'll talk about what we're doing on the 29th, but apart from that, with the Hair For Freedom, we had asked women to write letters to their MPs, as you mentioned, to put pressure on the government not to continue business as usual with the Iranian regime.

So, you know, to expel the ambassadors, to shut down the embassies because having a regime that legally kills women, it shouldn't be business as usual with that regime, you know? And I think the only way we can, in a sense, force the British government to take action is by public pressure, because it's not something they're going to do on their own. They're quite happy with things as they are.

And if there are any condemnations, it is as a result of pressure. And I want to give one example of how this pressure actually works. And you know, it's with the UN commission on the status of women, that Iran was on that commission. And it is the highest international body promoting gender equality, imagine. And the Islamic regime of Iran is on that body.

And as a result of pressure, Iran is the first state to have ever been removed from that body, the only state and the first state, even though you can be sure there are many others that need to be removed from that body, but it is because of public pressure.

And right now there's another campaign, which is calling for sex apartheid, or what some people call gender apartheid, but really it means sex apartheid, because now gender is so fraught, isn't it? But this term, gender apartheid has been used for decades, before this term became so fraught with other things. So, but really it's about sex apartheid, to be considered a crime against humanity.

And under international law, racial apartheid is a crime against humanity, but not sex apartheid. And so this campaign is calling for sex apartheid against women in Iran and Afghanistan to be considered a crime. So that's also a campaign that people can sign onto and support.

And the other areas, of course, refugee rights with this bill that the UK government is bringing forward, and it's called the Illegal Migrants Bill. It's as if you would call it the Scroungers Bill if you want to limit welfare rights or the, I don't know, you know, it's, sort of, the criminalising and dehumanising migrants that, sort of, making it seem like they're criminals, “Illegal Migrants Bill”.

Whereas, you know, asylum seekers in general flee without documents, and that's the reality, and it has been always, but it also will have an adverse reaction, consequence for women. So for example, with this bill, the protection that women have, pregnant women in detention have, that they can't be held for more than 72 hours, that will be removed and it can have huge effects on pregnant asylum-seeking women who are going to be detained and their babies. So it will also affect women asylum seekers.

It's something that people can also step up and oppose, because, don't forget those people who are being attacked in Iran, some of them at least will flee to reach safety. And so defending refugee rights is also an extension of defending women and people in Iran.

Freya: Definitely, and we can share all of those links as part of the podcast information, and we can talk more about that as part of the protest at the end of April, cause there definitely will be an action that women can take.

So if you aren't able to come to London and join the protest, please look online for the actions that you can take, which may be signing on to some of these campaigns, writing letters to MPs, and keeping that public pressure up. We have seen talk of, or heard talk of the government working out how they are going to designate the Iranian regime, the guards, as a terrorist organisation. I've seen talking or talks about that in the news, but we haven't seen any firm action.

Obviously, as we spoke about at the beginning of this podcast, tensions with Russia, tensions with China, it changes the dynamics of what's going on in the area, and we don't want to see a repeat of what happened 44 years ago. So we do need to keep that pressure up, and that's what we are here to do with our Hair for Freedom campaign and hopefully we can support you in doing so. I wanted to just step back one moment before we finish with details about the 29th.

You say that you are free to play music, to sing, to dance, to protest here in the UK, but what we have seen is fear of doing that as an Iranian woman, as an Iranian national who has family back home in Iran. I certainly know I have Iranian friends who say they cannot protest, they cannot join us on these protests, so they're so grateful to see women like myself, who don't have connections with Iran, don't have family we're worried about there, to come and protest, sort of, almost on their behalf cause they're unable to.

You've spoken out publicly about some of the threats that you've had against your actions, from the Iranian regime, but here in the UK. I wonder if you could share a little bit more about what it is like to be a dissident in the UK and to be shouting and using your freedoms here, in a place that still is hosting the Iranian regime within the embassy, and where we know there are these connections, where we are seeing attacks and threats to life, potentially to be being carried out on British soil or on European soil.

Maryam: I think, you know, the thing is that, all of us have family in Iran. I don't think there's any one of us who live in the diaspora, who don't have family in Iran. So I do think that of course what we do is risky for our families, but also as people who live in the diaspora who live in societies where we are free to protest, to a large extent that we have a responsibility to extend the voices of those who are fighting for the Woman Life Freedom Revolution in Iran.

So I do think that, you know, despite the risk, we should be intervening and standing up, and I think that there are a lot of ways people can do that as a way of safeguarding their own safety, and also their family abroad by hiding their faces, by being anonymous when they intervene on social media.

But I think we all have a responsibility to do that. I mean, for me, I've lived with threats for many decades, so it's not really something that affects me. I have a very good way of keeping out the bad and bringing in the good, you know, because I think it must be a way of surviving as well.

So for me, it’s not something that affects any decision that I make. And I think that it just comes with the territory, most probably. I think what I find different now, is that in addition to the Islamic regime, I am also getting threats from the very far right monarchist groups, who are, you know, they are our fascists really, the Iranian nationalist fascists.

So, that is a section of threats that I hadn't received before. So, but, you know, it's more of the same. I mean, obviously that's not to say that threats are not important. Of course they are, they have huge effects on people and they can be debilitating. It's just, it doesn't happen to me, for some odd reason. I just keep… I've got a really good way of compartmentalising things.

But I mean, I do have to say that I find that the police here don't take threats very seriously. I felt, you know, complete inaction on their part. And I don't really have any faith that they will act, but I think things are getting serious now because there's a lot of evidence that the Islamic Republic is planning assassinations and kidnappings from Britain as well as other countries.

And so hopefully they're going to be more vigilant. What I found quite astonishing is that one of the exile television stations that's based in London, that had received threats, is moving to the US because the police told them that they can't guarantee their safety. And I think that's quite a pathetic and absurd approach.

I mean, if British police can't protect people in Britain, then what is it going to be doing and what is it good for, you know, sort of thing. So that I find astonishing. If I was that TV program, I would refuse to move. I would refuse to move, and I would demand protection, because that's what they're supposed to do.

So, if they're going to just tell all of us to leave because they can't protect us from a foreign government, whose embassy by the way that they protect, so they are able to protect some things, aren't they? Interestingly, they can protect the repressive government, but they can't protect dissidents. It says a lot, I think, about political will, actually, cause that's what it boils down to, doesn't it?

Freya: It really does. And I think many of us have seen the way that the UK have both cosied up to, and at various times tried to distance themselves from, the Iranian regime, depending on what suits them at the time.

And as we've already covered a few times on this interview, with what's happening at the moment, they are definitely caught in a place where they are both wanting to cosy up to the regime, but also understanding the public pressure to do something, to put something in place, that shows that they are protesting or rejecting what the Iranian regime is doing internally.

But that is quite shocking to know that the police here in the UK are telling people like yourselves that they cannot be protected when they, like you say, they can protect an embassy from a few strands of hair, but they can't protect a television channel from threats to their lives.

So to continue that theme, and talking about the protests and how we can act in solidarity, what we can do here in the UK, we've got our protest on the 29th of April, the next one planned, as part of Hair for Freedom.

Now this protest has changed. It started off with us cutting hair. It then was supposed to be throwing hair, but we're finding something else to do with that hair, we were unable to throw it as we've discussed, we're looking at art and all sorts of things.

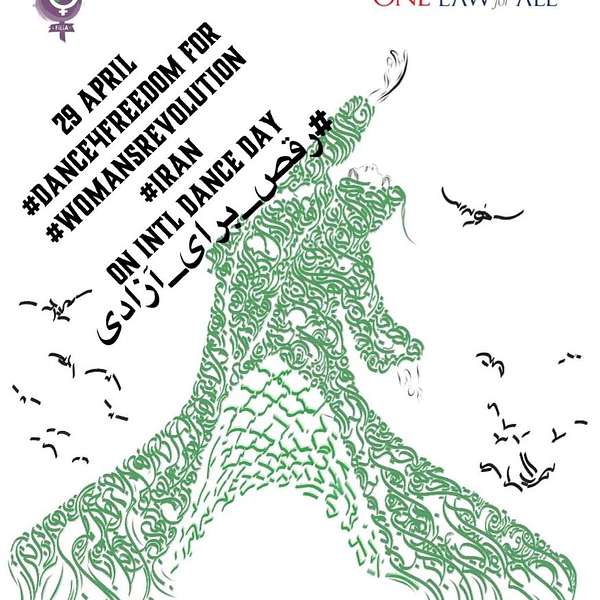

The protests have changed in Iran as well. And now what we are looking to do on the 29th is a dance-in. We are going to be dancing for 45 minutes as part of our protest at Piccadilly Circus. So I wonder if you want to share with everyone what we're planning on doing, and how the protests have changed and why the protests have changed.

Maryam: Well, protests in Iran are not, you know, we don’t see the mass protests in various cities across the country, as in the past. We are seeing protests, of course, for example, every Friday in Baluchestan, which is one of the most impoverished and repressed regions of Iran. And we also saw protests during Nowruz, which is the Iranian New Year, but also other New Years too, Kurdish and Tajik.

And it’s the day that spring comes, so it's actually not an Islamic holiday. It comes from before Islamic rule in Iran. And it also is something that the regime tried to ban, celebrating Nowruz, because it wasn’t Islamic, but no one listened. And so that day was also a day of protest. And people have been protesting in various ways, including, like I mentioned, when Sepideh Qoliyan out of prison, continuing to say slogans and show their defiance, or at funerals or 40 days after a funeral of someone who's been killed, these have become centres of protests.

And also people have been dancing on the streets, walking without the veil. And we know that people who have done footage of themselves dancing have been arrested. One couple got 10-year prison sentences each for doing a dance. And so we thought that on April 29th, it's International Day of Dance, that we will have a dance-in, kind of like a sit-in, but a dance-in, and we're going to dance for 45 minutes. It's going to be protest dancing, in solidarity with the Women's Revolution in Iran.

And the 45 minutes is to honour Mahsa Amini, because she was, she had collapsed, as you mentioned earlier, at the morality police's headquarters, and for 45 minutes they mocked her. They said she was a Bollywood actress. All the while other women were pleading that they take her to hospital, and they only called for an ambulance after 45 minutes of her lying there.

And so it’s symbolic. The 45 minutes will be symbolic. And the dance-in will be just, you know, something that women are not allowed to do. They're not allowed to dance. And so we will dance for our sisters in Iran, and to keep attention on this revolution, which we all need to win, because it will mean a great deal, not just for women there, but for women everywhere.

Freya: I'm really looking forward to it. I've seen videos throughout the years before this revolution sparked of women dancing in Iran, women dancing on rooftops, women dancing without the hijab, and it's been incredibly moving, and so I'm very excited to be there and to dance with you.

Just for our listeners, for those of you that perhaps like myself, might have dodgy hips and knees and backs and all the rest of it. If you need to sit down and dance, that's absolutely fine. There's plenty of steps that we can sit on. Maybe we'll even ask the choreographers to teach us some sit-down dancing when we get to that point.

I think that's probably the end of our time that we have here today. Is there anything that you would like to add to what we've discussed today, of what we can do here, as your sisters in solidarity?

Maryam: Definitely try to come to the dance-in if you can. It will be, I think, another one of those moving actions like we had at Piccadilly Circus, in Hair for Freedom. So come to the dance-in, and as you said, Freya, we can dance sitting down as well.

And carry on, you know, highlighting what's happening in Iran. If someone's arrested, if someone has been killed. Writing to MPs, continuing to do that, continuing to put pressure on the UN to consider sex apartheid as a crime against humanity. There's so many things we can all do in order to just keep pressure on.

And I think, you know, we all know that when people are risking their lives by going out in the streets, by shouting slogans, by dancing, even, by walking unveiled, that it gives them a lot of hope and courage and encouragement to know that there are people, you know, in other countries that care about what happens to them. So I think the, sort of, public dance-in will be really good news for women in Iran. And so we want to try to make sure that as many of us are there as possible.

Freya: Fantastic. Thank you so much. And again, for those listening, if you're not able to make it to London, please send in videos of you dancing. We will be sharing information around hashtags you can share that under, and we will collect those videos, and we will make one long FiLiA video celebrating everyone dancing.

And to those listening as well, please know that our actions here are being seen and heard cross the Middle East and through Persian television. I know that our Hair for Freedom campaign was seen out there, and we've had messages telling us that they've seen it and they've felt, women in Iran have felt supported by it, which is really wonderful to hear.

Thank you so much, Maryam. We really appreciate your time and I look forward to seeing you again in person on the 29th of April.

Maryam: Yes, thank you, Freya as always. And yes, it's, yeah, looking forward to the 29th. Thank you.

Freya: Thank you.